In a new study, physicists at JILA and the University of Colorado Boulder have used a cloud of atoms chilled down to incredibly cold temperatures to simultaneously measure acceleration in three dimensions—a feat that many scientists didn’t think was possible.

The device, a new type of atom “interferometer,” could one day help people navigate submarines, spacecraft, cars and other vehicles more precisely.

“Traditional atom interferometers can only measure acceleration in a single dimension, but we live within a three-dimensional world,” said Kendall Mehling, a co-author of the new study and a graduate student in the Department of Physics at CU Boulder. “To know where I'm going, and to know where I’ve been, I need to track my acceleration in all three dimensions.”

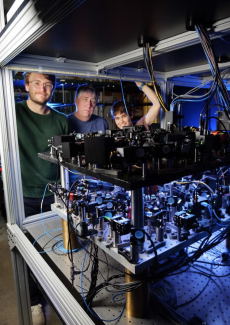

The researchers published their paper, titled “Vector atom accelerometry in an optical lattice,” this month in the journal Science Advances. The team included Mehling; Catie LeDesma, a postdoctoral researcher in physics; and Murray Holland, professor of physics and fellow of JILA, a joint research institute between CU Boulder and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

In 2023, NASA awarded the CU Boulder researchers a $5.5 million grant through the agency’s Quantum Pathways Institute to continue developing the sensor technology.

The new device is a marvel of engineering: Holland and his colleagues employ six lasers as thin as a human hair to pin a cloud of tens of thousands of rubidium atoms in place. Then, with help from artificial intelligence, they manipulate those lasers in complex patterns—allowing the team to measure the behavior of the atoms as they react to small accelerations, like pressing the gas pedal down in your car.

Today, most vehicles track acceleration using GPS and traditional, or “classical,” electronic devices known as accelerometers. The team’s quantum device has a long way to go before it can compete with these tools. But the researchers see a lot of promise for navigation technology based on atoms.

“If you leave a classical sensor out in different environments for years, it will age and decay,” Mehling said. “The springs in your clock will change and warp. Atoms don’t age.”